Giving our drone sight – how we taught it to find probes

Modern drones are often flown by following predefined waypoints, i.e. fixed positons in space that are visited sequentally. This provides a short context for what “waypoints” mean in the following.

We wanted the drone to do more than follow waypoints. It needed to see – to identfy ground probes, estmate where they are in meters, and hand clear, usable positons back to our mission logic. The result is a compact vision pipeline that blends modern object detecton with classical geometry and a likle statstcal smoothing – simple in concept, powerful in practce.

We started with data. Images were annotated in Roboflow to get consistent, high-quality bounding boxes for the probe types we care about. That foundaton made training straigh forward: after an inital run we finetuned the best model at higher resoluton to capture subtle visual cues on the ground. Training on a local machine (using Apple’s MPS backend for speed) let us iterate quickly and keep the model small and responsive enough for onboard inference.

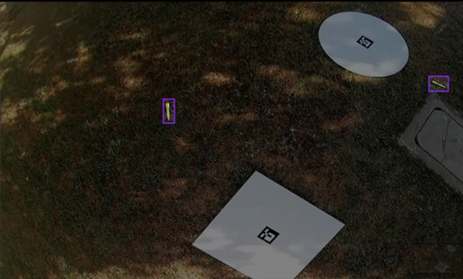

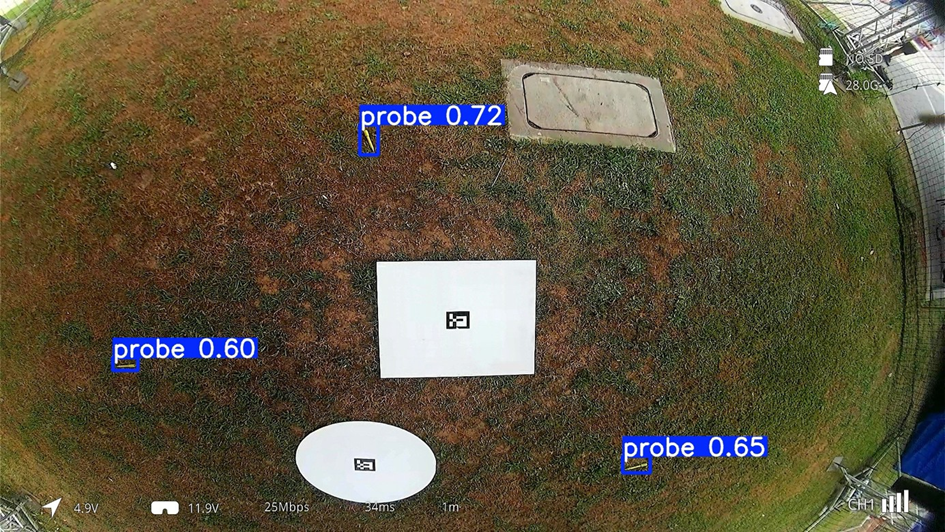

Detecton is handled by a YOLO model tuned for the job. YOLO gives us reliable bounding boxes and confidence scores in realtime, which is essential for an in-flight system. But a box on the image is only half the story – the drone needs a metric positon. For that we combined two ideas that complement each other nicely.

First, we use ArUco tags placed at known locatons as anchors. ArUco gives us a pose estmate for a visible tag (positon and orientaton) which we treat as the local origin and reference yaw. Second, for each detected probe we estmate depth from its apparent size (we know roughly how long the probe is in the real world) and back-project the pixel into the scene. Combining the tag-based pose and the pixel projecton yields an (x, y) positon on the ground plane in meters relatve to the start tag – exactly the format our flight logic expects.

Raw detecton is noisy, so we use lightweight filtering and clustering to produce stable results. Detectons are checked by confidence and depth tolerance, then aggregated over time. During calibration, clustering parameters and thresholds were determined empirically through repeated test runs rather than being predefined. During operaton we cluster recent detectons and pick the top three candidates based on detecton count and proximity rules. This gives operators and the mission planner a short list of robust probe locatons instead of a stream of jittery points.

We also built in safety: distance limits for reliable projecton, geofence checks, and a small temporal threshold (require multple hits before acton). Those measures stop the drone from chasing false positves or venturing outside safe zones.

The end result: a drone that extends a classical waypoint-following mission with visual percepton. It detects, localises, and hands off a small set of trustworthy probe positons – fast enough for practcal missions, and robust enough for field tests. For teams in the tech industry, it’s a good example of pragmatc vision engineering: combine modern ML for percepton, classical geometry for metric grounding, and simple statistics for stability – and you get useful autonomy without overcomplicating the stack.

Comments

No comment posted about Giving our drone sight – how we taught it to find probes